No Time To Mourn

It all started with a call from Meredith the hairdresser. My mother made an appointment that week, and she hadn’t shown up. She hadn’t called to cancel, and Meredith had been unable to reach her. She was growing worried, and left a voicemail for me hoping there was a simple explanation. I hadn’t realized my mother had left an emergency contact number with her hairdresser—I didn’t know that was a thing. I was also unaware that her emergency contact was me.

I called Meredith back, and she was already on the phone with the local police department. Maybe she was visiting my sister and my aunt in California? Maybe she was staying with friends somewhere and forgot to cancel? I answered the questions with my own “maybe,” but I’m certain I didn’t sound convincing. My mother, now living alone at age 82, didn’t travel anymore. She didn’t go stay with friends. And if you called her, she called you back. I promised Meredith and the police officer I would call both my mom’s numbers, my sister, and anyone else I could think of to see if they knew anything. Meredith kindly hoped someone would know where Mom was. I said–rather weakly, I imagine–me, too.

Of course, my sister and everyone else I reached out to had no idea. No, I hadn’t heard from her. Was going to call her this weekend. Should I stop by? Each response only strengthened my intuition about what had really happened. I called the police officer back: no one has heard from her. He respectfully asked my permission for a forced entry. He didn’t actually need my permission, but I was grateful for the gesture. I had a sense this wasn’t the first time the officer had been on a call like this. He told me he’d call me back once he was inside.

I waited, clinging on to a tiny bit of hope provided by Meredith, that it was all some mistake. But I knew what the officer would find. The only questions was what room was she in.

Then the answer came: the living room, in her favorite recliner. It looked peaceful, the officer told me.

I called my sister back and gave her the news. Seventeen years earlier, she had the unenviable task of telling me our father had passed. This time, it was my job to tell her about Mom. I suppose there is some fairness in that.

Several more frantic phone calls, the location of a cheap flight online, and a trip down to my classroom to prepare six days of sub plans, and I was suddenly on my way to Colorado. My sister would fly out from San Diego the same day, and Darlene would fly out from New York. We would all connect at the airport in Denver. Not the ideal circumstances for my sister and Darlene to meet, but life doesn’t always provide ideal circumstances. My sister’s husband would arrive the next night. The good news is both my sister and I would be with the people we loved the most in the world. We would both need it.

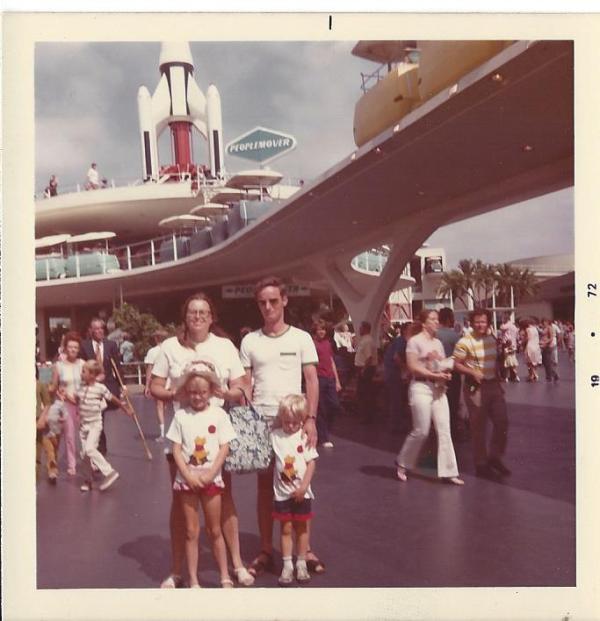

My parents, sister and myself at Disneyland, summer 1972.

So the four of us were there ostensibly to mourn my mother’s passing, but there is no space for that. Death is complicated in the developed world. Sadly, we don’t have a culture that tells us, “take several days to mourn. Visit with friends and family. When she is buried, then you can take care of the business.” No, the business comes first.

First, locate the will, and all of the other pertinent documents. Contact the bank, the credit card, the pension fund, the life insurance, social security, the mortgage company. If you don’t, the creditors come after the next of kin. If you don’t cancel the pensions and social security, they want to be refunded for any paid out after the death. Then there’s the cable company, the electric company, the magazine subscriptions. Economic lives are complicated, and they don’t unravel easily. Your time is taken up with all of these tasks. On the one hand, you feel useful, it gives you something to focus on. On the other hand, you aren’t processing any of your grief.

Death is also expensive. Aside from bills you inherit as next of kin (bills always come before any assets inherited), you have to visit a funeral home. The people at the funeral home are very nice, speak in soft voices, and say all the right things. But they still wanted $2000 to cremate my mother. As kind as they are, and as necessary as they are, they are still profiting from her death. There’s no way that’s going to sit well with me.

Then comes the erasure. The personal belongings have to go. Multiple trips to Goodwill. A call to the Restore to arrange furniture pick up. A few items shipped home. Food has to be eaten, and what cannot is thrown away. Dumpsters get filled, and filled again. Each day that passes, more and more pieces of my mother’s personality are deleted: the furniture, the Monet and Toulouse-Lautrec paintings, the books, the magazines, the photographs, the crossword puzzles, the bear, frog, and cat themed chachkies. All of the things that made it a home. They all disappear gradually before your eyes, then before long you are standing in an empty home.

It’s not your home; you didn’t get to build it, but you get to take it apart. A meeting with the realtor to arrange the sale of the home, and the dismantling is complete. When you leave a house, you usually are on your way to someplace else. You take your home with you. Sure, things are in a different place, but you are still surrounded with the familiar. It’s on odd feeling to erase a home–especially one that isn’t yours.

None of the things that need to be done are really about mourning. How do you mourn when you don’t have the time?